Stage 4 Lung Cancer Survival Rates and 2026 Treatments in the United States Including Immunotherapy

Five-year relative survival for stage 4 lung cancer in the U.S. is roughly 12% for non‑small cell and about 4% for small cell. This article summarizes these statistics and 2026 treatment advances, including targeted therapies and immunotherapies, to inform patients and caregivers.

Stage 4 Lung Cancer Survival Rates and 2026 Treatments in the United States Including Immunotherapy

Facing stage 4 lung cancer can feel overwhelming, especially when trying to understand survival statistics and rapidly evolving treatment options in the United States. While stage 4 usually means the cancer has spread beyond the lungs, new therapies such as immunotherapy, targeted drugs, and more sophisticated use of chemotherapy and radiation are changing outcomes for some people and reshaping care as we move through the mid‑2020s.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.

Advances in treatment for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) grows and spreads quickly, and extensive-stage disease means it has moved beyond one side of the chest. For many years, the mainstay of treatment was combination chemotherapy, typically a platinum drug such as carboplatin or cisplatin plus etoposide. This regimen can shrink tumors rapidly and relieve symptoms, but responses often do not last long, and relapse is common.

In the United States, adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy has become a key advance for extensive-stage SCLC. Regimens such as atezolizumab plus carboplatin and etoposide, or durvalumab with similar chemotherapy, have been shown to extend overall survival compared with chemotherapy alone in large clinical trials. After the initial cycles, patients who tolerate treatment may continue on maintenance immunotherapy as long as it remains effective and side effects are manageable.

Radiation to the chest or to specific areas of spread, such as the brain or bones, can be used to control symptoms or target remaining disease. Approaches to preventive brain radiation are evolving, with more frequent use of MRI monitoring to balance benefits and potential side effects. Clinical trials are exploring additional combinations and novel agents that might further improve long‑term control for extensive-stage SCLC.

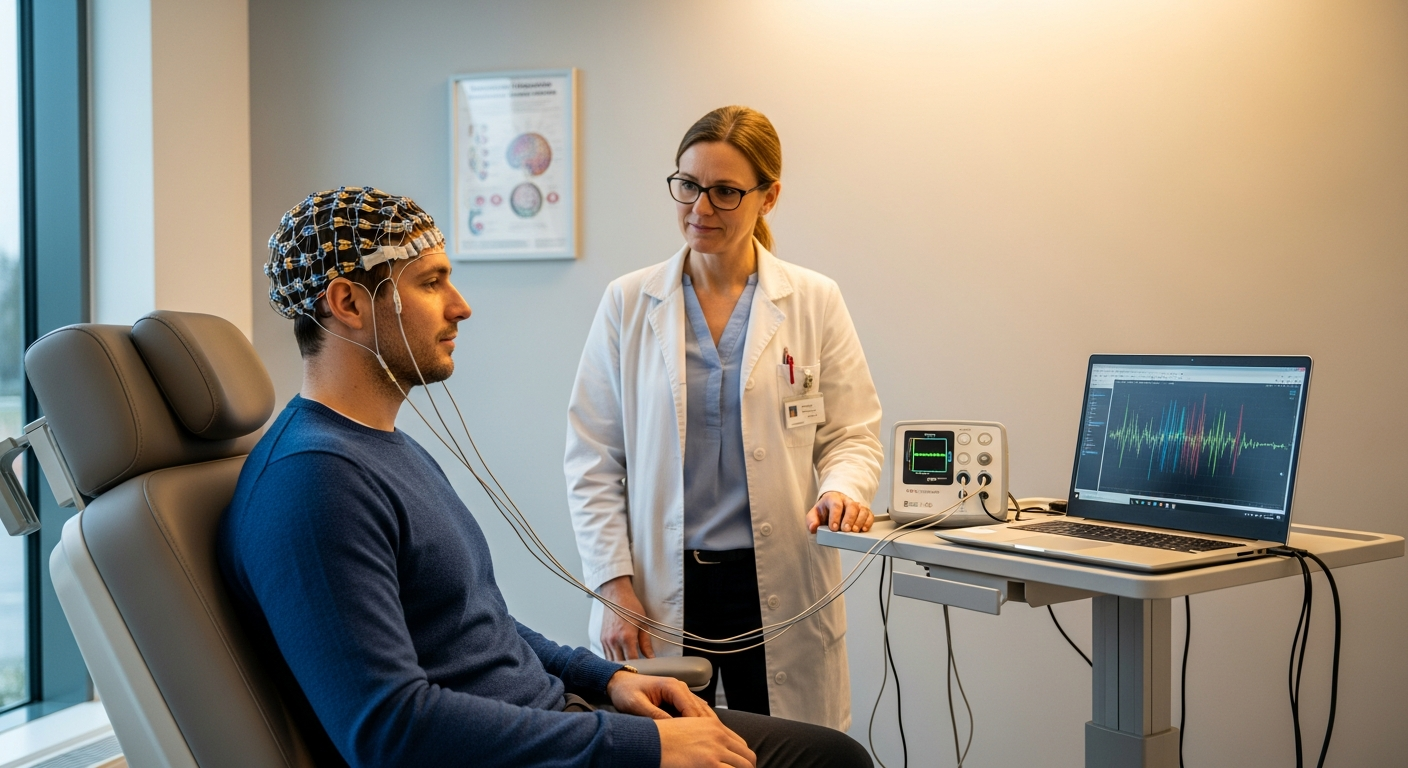

Immunotherapy: harnessing the immune system

Immunotherapy aims to help the body’s own immune system recognize and attack cancer cells more effectively. In lung cancer, the most widely used form is immune checkpoint inhibition, which targets proteins such as PD‑1, PD‑L1, or CTLA‑4 that normally act as brakes on immune responses.

For many people with advanced non‑small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) without a targetable mutation, drugs such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab, atezolizumab, or durvalumab are now part of standard treatment plans. Depending on the tumor’s PD‑L1 level and other factors, immunotherapy may be given alone, combined with chemotherapy, or used after chemoradiation to help keep the cancer under control.

Immunotherapy can lead to long‑lasting responses for a subset of patients, sometimes measured in years rather than months. However, not everyone benefits, and immune‑related side effects can affect organs such as the lungs, liver, thyroid, skin, or intestines. These effects are often manageable if recognized early, but they require close monitoring and prompt attention from oncology and supportive‑care teams.

As research continues into 2026, combinations of immunotherapy with targeted drugs, chemotherapy, or novel agents are under active study. New biomarkers beyond PD‑L1, and a better understanding of the tumor microenvironment, may help clinicians refine who is most likely to respond to specific immunotherapy strategies.

Targeted therapy: precision medicine in action

Targeted therapies are medicines designed to block specific genetic changes or signaling pathways that drive cancer growth. In metastatic NSCLC, especially adenocarcinoma, testing can reveal alterations such as EGFR mutations, ALK or ROS1 rearrangements, BRAF V600E, MET exon 14 skipping, RET or NTRK fusions, and KRAS G12C, among others.

When such an alteration is found, an oral targeted drug is often chosen as the first systemic treatment. Examples include EGFR inhibitors, ALK inhibitors, and KRAS G12C inhibitors, which can significantly shrink tumors and help people feel better quickly. Some newer agents have been designed to cross the blood–brain barrier, offering improved control of brain metastases compared with older drugs or chemotherapy.

Over time, cancers can develop resistance to a targeted therapy. In these situations, oncologists may recommend repeat tissue biopsy or liquid biopsy to look for new resistance mutations and identify the next line of treatment. As more targeted options become available, treatment planning increasingly resembles a sequence of tailored therapies rather than a single fixed regimen, particularly in specialized cancer centers.

The role of comprehensive genetic testing in treatment decisions

Because targeted therapies depend on finding specific molecular alterations, comprehensive genetic testing is now central to managing stage 4 NSCLC in the United States. This usually involves next‑generation sequencing of tumor tissue, a blood‑based liquid biopsy, or both. Panels can evaluate dozens or even hundreds of genes at once, improving the chances of detecting an actionable change.

Guidelines generally recommend broad molecular testing for people with advanced non‑squamous NSCLC and for selected squamous cancers, especially in younger patients or non‑smokers. In addition to mutation testing, clinicians often assess PD‑L1 expression to guide immunotherapy choices. The results help determine whether targeted therapy, immunotherapy, chemotherapy, or a combination is most appropriate at a given time.

Access to timely, high‑quality testing can influence outcomes. Delays in obtaining or analyzing samples may postpone optimal treatment, and disparities in access can affect certain communities more than others. Efforts across the US healthcare system are focused on standardizing testing, improving coordination between community clinics and specialized laboratories, and ensuring that patients understand what their results mean for current options and potential clinical trials.

Understanding stage 4 lung cancer survival rates

Survival statistics for stage 4 lung cancer are often quoted as averages based on large groups of patients, and they cannot predict what will happen for any one person. In US data from the past decade, the five‑year relative survival rate for distant‑stage NSCLC has been in the single‑digit percentage range, while extensive‑stage SCLC typically shows even lower long‑term survival. These numbers, however, reflect patients treated over many years, including before the widespread use of modern immunotherapy and targeted therapies.

Outcomes vary greatly depending on tumor type, genetic profile, overall health, response to treatment, and access to specialized care. Some individuals, particularly those with targetable mutations or strong responses to immunotherapy, now live substantially longer than older statistics might suggest. At the same time, others may face more aggressive disease that progresses despite multiple treatments.

When discussing survival, oncologists often use terms such as median survival, progression‑free survival, and overall survival to describe how long groups of patients lived or remained free from worsening disease in clinical trials. Quality of life is also a crucial consideration. Integrating palliative care early, managing symptoms proactively, and supporting emotional and practical needs can help people live as well as possible, regardless of the specific survival numbers.

In the context of evolving treatments through 2026, the overall picture for stage 4 lung cancer in the United States is one of gradual improvement, driven by better systemic therapies, more personalized decision‑making, and greater attention to supportive care. Survival statistics remain serious, but they are only one part of a larger conversation that includes goals, values, and the full range of options available for each individual.